We recently caught up with 2022 Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize Finalist and TMR contributor Carolyne Wright, whose latest book is Masquerade: A Memoir in Poetry (Lost Horse Press, 2021). In Part 1, Wright takes us through the challenge of wedding poetic lyricism to social engagement, or in other words, getting poetry that is committed to witnessing contemporary and historical issues to also remain committed to the opportunities for heightened, musical language to which lyric poetry is heir.

Along the way, she gives us a rich annotation of the poems which were recently finalists, which gives us a lot more insight into the historical and regional contexts for the poems, and a wonderful beginning foray into the complex histories and politics of Chile and Brazil. Part 2 (coming soon!) will focus more on her individual process and ancestry as a writer, with additional insight into the work of translation.

The Missouri Review: In praise of your collection, This Dream the World, Robert Cording said, “Carolyne Wright’s poems connect the personal and political and walk the difficult edge of poetic lyricism and social engagement. They are poems that search for ‘a language between us’ in which personal loss becomes a metaphor for an injured and debilitating world where political violence and conflict keep us from fulfilling ourselves in meaningful ways.” I saw this tension between personal and political in your poem, “Errância: The Caravan,” which was a finalist for the 2022 Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize. Can you talk about your conception of the relationship between “poetic lyricism” and “social engagement”?

Carolyne Wright: What a great question with which to begin! I love Robert Cording’s phrasing in that comment of his, and very much appreciate his praise. When I first began seriously reading and writing poetry, in high school, I remember noting how so much anti-war poetry, even by the poetic luminaries of the day (poets I very much respected) was rather didactic and free of imagery and musicality, as if when poets confronted political matters, the nuanced, vivid and rhythmically varied diction that charged their other work just went away. Their poems protesting the Vietnam War were big on social engagement, but the prosodic and lyric engagement was absent—the language was impassioned but flat. I wondered if poetic lyricism and social engagement could co-exist in the same poem; or was political poetry supposed to be mere “podium pounding.”

The first answers to this question came after I completed my undergraduate degree and spent a year in Chile on a Fulbright-Hayes Study Grant during the presidency of Salvador Allende, the democratically elected head of the Unidad Popular (a coalition of center-left and left-wing parties, similar to the social democratic coalitions that govern in many European countries, governments which the U.S. does not attempt to overthrow). As all the world knows, on the first 9-11—September 11, 1973—Allende was overthrown in a military coup supported and, to some degree orchestrated by the U.S. government under the leadership of those unindicted war criminals Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger. In fact, the first memoir essay I published about this time in Chile, “El Compañero Presidente,”as published in . . . the Missouri Review! I still recall with fondness and gratitude all the comments and suggestions that Speer Morgan—still the Editor!—made on this piece.

During that year in Chile, I became concientizada, as Chileans say: made politically aware, socially conscious—what some now call woke! In the original Spanish, I read the lyrically charged and socially engaged poetry of Pablo Neruda and Nicanor Parra, among others; I listened to the songs and studied the lyrics of Victor Jara, Isabel and Ángel Parra, the surviving children of Nicanor Parra’s younger sister Violeta Parra (1917-1967), now universally acknowledged as the mother of La Nueva Canción, and in my opinion a more powerful poet, much more grounded in the life of the Chilean people, than her long-lived older brother. I loved how all these poets could present issues of great political and social concern in powerful imagery and lyrical language, not to mention song. In this work, I could see and hear and feel the individual Chileans, farmers and fisherman and miners, weavers and healers and teachers, portrayed in these poems and songs. I could see the fields and mountains, the villages and towns, the seacoasts and northern deserts, of this proud and enterprising country. I also came to perceive how most policies or political actions in Chile had immediate, visible effects in the personal lives of the citizens. In that era, there was no widespread sheltering affluence, as in the U. S., to diffuse public attention or provide economic buffering from the way that larger public events impacted peoples’ lives. So I determined that the poetry I wrote about Chile, as well as what I wrote about my own country (whose politics I now saw with very different eyes), would be both imagistically vivid and lyrically charged.

To consider one example among the poems I sent for the Editors’ Prize—all poems set in the other country of South America and the global South that has had such a powerful influence on my imagination, Brazil! “Errância: The Caravan” was a poem I drafted quickly, in response to the comments by Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino, about the imagery she had had in mind for her sculptural work—of the dry, impoverished, Northeast interior region of Brazil. This is not a region of Brazil I have visited, but its frequent droughts have made for ongoing environmental problems for decades, and the waves of migrants departing the region to look for work in the big cities farther south, have been a persistent theme of Brazilian literature, music, and films, much as the Dustbowl of the 1930’s Depression era continues to resound in North American culture and literary imagination. In Portuguese classes I had read a good deal and seen Brazilian films that featured impoverished rural people (os retirantes, as they are called in Portuguese) fleeing that dry Northeastern region of Brasil called the sertão.

In fact, as I started this poem, I had in mind an image from the opening of a Brazilian film I had recently seen, of a caravan of retirantes straggling, on foot and horseback, across a vast stretch of blinding, white sand. And I thought of the iconic song, “Asa Branca” (White Wing) the most famous composition by the beloved singer-composer from the Northeast, Luiz Gonzaga—one of the first songs I heard the first time I was in Salvador, Bahia, decades ago. I had always loved it, so I quoted the first two lines of the lyrics in the original Portuguese. In English: “When I saw the land was burning / like the bonfires of São João.” The poor man from the rural Northeast has lost his cattle and horses, and he has fled the sertão, like the asa branca, the white-winged picazuro pigeon native to the region; but he promises his beloved Rosinha that he will return when the rains fall and the fields of the sertão turn green again. As I wrote, the retirantes in the caravan of this poem began to appear to me more like penitents in some romaria, some religious procession, and the prosperous cities of the south like walled paradises that slammed their gates shut on these poor pilgrims.

TMR: Can you describe the genesis and development of the poems in the packet you submitted for the Editors’ Prize?

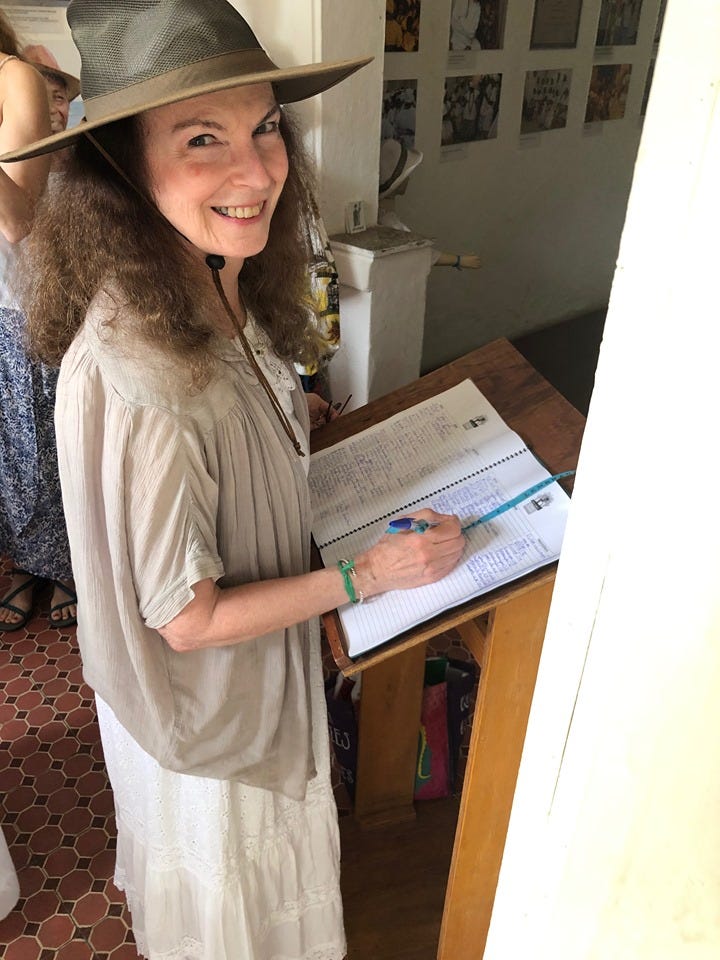

CW: Oh thanks so much for your interest in this group of poems! They form part of a series with the working title of Solstice in the South—this series had its genesis during the 2018 artistic residency I was honored to spend at the Instituto Sacatar on the island of Itaparica, Bahia. This residency was a dream come true for me, because I have loved Brazil since my first visit decades ago. These poems were inspired by the human and cultural life, as well as the natural history of Brazil, especially Bahia—not only the city of Salvador and the semi-rural island of Itaparica, but also by the plants, animals, birds and marine life. This project is my poet’s way to continue to dwell with the human and natural world of Bahia, as it has inhabited and continues to inspire my work.

I arrived at Sacatar fairly fluent in Brazilian Portuguese—after studying the language for a few years at the U of Washington, reading stories and novels by Brazilian, Moçambican and Angolan authors in the original Portuguese for those classes, and doing Afro-Brazilian dance in Seattle with teachers from Bahia. I was fortunate also that there was one fellow Sacatar resident, a photographer from Salvador, who spoke no English. It turned out that I was the only resident who spoke enough Portuguese to carry on conversations in depth with him, about the arts, politics, family, the human nexus! So he and I talked a lot, which greatly improved my Portuguese and helped me to stabilize the regional accent (Bahian!) with which I speak the language. To be able to speak and understand the language being spoken around me, and the folk / popular as well as literary culture embodied in that language, really enables me to enter into the culture on its own terms, as much as possible, all of which informs this series of poems.

This is not the first group of poems I have written about Brazil. The earlier ones were written about my first encounter years ago with Salvador, Bahia and other places in Brazil—I remained fascinated with Brazil ever since then. These earlier poems were included in my book, Seasons of Mangoes and Brainfire, which as a manuscript received the Blue Lynx Prize and was published by Eastern Washington University Press / Lynx House Books (second edition, 2005). As a book, it was awarded the Oklahoma Book Award in Poetry and an American Book Award—one of the most important awards for a book with socio-political themes and resonance. During the Sacatar residency in 2018, I worked with Marcelo Thomaz, Communications Director of the Instituto Sacatar, to translate these earlier poems about Brazil to Portuguese; then my photographer colleague also took an interest and gave some suggestions on my translations of the first poems I wrote at Sacatar.

Okay, the poems themselves! The only pre-Sacatar poem in the group I sent is “Ghazal: Miss Bishop Dances the Samba,“ informed by my close reading of Bishop’s life and work, my study with her for that one quarter at the University of Washington in the year after my first travels to Brazil, my yearning to have spent more time in her presence during those several weeks, and my imaginatively entering into her life in Brazil. Miss Bishop spent the better part of 15 years, between 1952 and 1967, in Brazil, with the brilliant, aristocratic woman who was the love of her life, Lota de Macedo Soares. I made this poem a ghazal, turning on the refrain “dance the samba,” because I have a sneaky suspicion, that Miss Bishop did not, in fact, dance, not even the samba! She was the most unlikely (to use her own term) person to be in close communion with that aspect of Brazilian culture.

This ghazal, along with the two Errância poems, exist in Portuguese as well, as translated by me in collaboration with Emanuella Leite Rodrigues de Moraes (a post-doctoral research fellow from Bahia by way of Rio de Janeiro, at the University of Washington in 2018-2019, who became a collaborator and good friend), with suggestions as well from Décio Torres (poet, fiction writer and Professor Emeritus from the Universidade Federal da Bahia) and Marcelo Thomaz. Making my own writing about Brazil available in Portuguese for a Lusophone readership, in particular the poems of Solstice in the South / Solstício no sul, was part of the project for which I received a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award to Brazil, which took me back to Salvador, Bahia for two months last year and for another two months in the near future.

The two Errância poems emerged from a sort of commission. In October 2018, I was invited by Hauser & Wirth Gallery in NYC (in conjunction with the Poetry Society of America) to write a poem in response to a work of art in an upcoming exhibit by Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino. The poem would be printed on a card featuring the artwork on one side and the poem on the other, and it would be free to gallery visitors. The hope of gallery staff was that the poem would enter into dialogue with the artwork and provide an additional way of viewing or experiencing the artwork while also occupying a space outside of the physical gallery.

The first poem, “Errância: Late Afternoon,” was to respond to a sculptural work in Maiolino’s new exhibit at Hauser & Wirth, Errância Poética (Poetic Wanderings), from Da Terra series. This was an amazing confluence, because I had only recently returned from the two months’ residency at the Instituto Sacatar, and my thoughts were full of imagery of Bahia, and the sounds and rhythms of Bahian Portuguese. This poem’s errância takes place on Itaparica, and incorporates terms and materials from Maiolino’s artwork—tactile images, shapes, and textures—as well as the human inhabitants, possibly artists of Sacatar, who are moving through the landscape of the poem.

After I sent this poem to my contact at Hauser & Wurth, he wrote back to say that the artist had seen it, and had said something to the effect that for the sculptural piece to which I responded, she had had in mind imagery of the dry, impoverished, Northeast interior region of Brazil, where the hot sun bakes the clay-based earth and creates cracks and shapes similar to her sculpture. Clearly, my poem uses a good deal of imagery of the littoral, the lush, coastal regions of Bahia, but it was too close to the date of the exhibit for me to write and submit another poem. The gallery had to go with the poem that they had. But Anna Maria’s comments sparked the second poem, “Errância: The Caravan,” which I wrote quickly, and have described above.

“An Act of Kindness in Bahia” recalls one afternoon early in my time at Sacatar, when I headed off on my own to the center of Itaparica town, to shop for a specific item—a white skirt to wear for a ceremony of the Eguns that would take place that evening. (It was an honor to be invited to this ceremony, by one of the Sacatar employees who was an active member of the Egum community, and we artist residents who accepted the invitation intended to honor the practice of wearing white!) But in this rural island town with few street signs, when I reached the main road, I turned left instead of right and walked for quite a ways away from town, before I decided to ask directions. I had been at Sacatar long enough to realize that the local people of the island spoke Portuguese with a different accent than the city people of Salvador, and I could barely understand them! If I asked directions, they could understand me, but I would not be able to understand their replies! That was my basic shyness, but the people of Itaparica (most of whom speak only Portuguese) were very kind and patient with those like me from elsewhere; and the woman who walked and chatted cheerfully with me for those few blocks as I walked in the wrong direction, simply included me in her walking and talking. I did ultimately ask for directions from a few other local women whom I passed on the street, and I finally reached the center of town, where in one of the few shops catering to tourists, I found a white skirt for the ceremony. Most of the details of that afternoon walk and shopping venture are not in the poem—a free-verse, lyric narrative which focusses on the walk itself, the sights and sounds and imagery of the neighborhood through which I walked, on the encounter with the cheerful lady who shared her umbrella with me, my efforts to understand and guess at what she was saying. But it was a pleasant challenge to get lost and then unlost in parts of the working-class Itaparica community that I had not experienced before.

“Ghazal: Friends” plays on the contrast between island and city (in this case, Itaparica and Salvador; but the rural and urban polarities could be represented by any island, any city) to underscore the transformation a friendship that began on the island undergoes when it attempts to continue in the city but ends instead, far from its Edenic genesis. This dramatic situation called for a stripped-down, understated treatment and close focus, which the ghazal readily provides, with its refrain / repetitions at the conclusion of every couplet. I had actually written a pantoum about this friendship and its jarring conclusion; but in that form the poem got too convoluted and introduced too much inessential detail. But I may go back and work on the pantoum version again – it can be a fun challenge to treat the same subject matter more than once, as painters and photographers often do.

“Choices / Encontros Binários” is inspired by and modeled on “Choices” by poet colleague and friend Lynn McGee, a poem she had posted on her Facebook timeline. In the epigraph to “Choices,” Lynn attributes its genesis to an episode of a Netflix series in which the protagonist must play an interactive game of binary choices. Ah, I thought, as my poetic antennae began to waggle! I could write what I call a “poetic palimpsest” in response! I also call this process “The Poet Writes Back / The Poet Strikes Back”: a poem written in response to an earlier poem, often in the form or rhetorical patterning of that model poem, always with acknowledgment, and with permission from the author of the original, if that person is living and able to be contacted. (Lynn said Yes!) My poem would be transposed to a setting in Bahia, signaled in part by the Portuguese part of the title— Encontros Binários—and like Lynn’s poem would conclude with a binary choice that is implicitly “decided” by being repeated. The binary choice repeated in my poem is to “wait for the ghost girl,” an image that occurs at the beginning and again at the end of the poem. According to stories I heard at Sacatar, the ghost of a young girl appears at dawn or dusk to some residents, sitting at the end of that resident’s bed. Since Sacatar’s main house, the casarāo or casa grande, was originally built as the summer residence for students of a convent school in the city of Salvador, ghosts of young girls are not so unlikely!

“Eguns”: I was intrigued by these ancestral spirits celebrated in elaborate, all-night rituals now practiced only in a few traditional communities in Benin and Nigeria, and in Afro-Brazilian communities on the island of Itaparica, Bahia, Brazil. I attended only one ceremony during my time at Sacatar, at one of the main terreiros (ceremonial centers) on the island only a few miles down the road from Sacatar. That will be the subject of other writings! But later I read a memoir in progress, After the Eguns, by Taylor Van Horne, Co-Director of Sacatar, with whom I had hit it off during my residency. He appreciated my comments and suggestions on this manuscript, and I was fascinated by his many experiences with the Egum communities—the force and vividness of the rituals, the personalities of participants and practitioners, the history of struggles to maintain these traditions in the face of persecution from the Catholic Church and the police, and more recently, harassment from converts to the fast-growing, aggressive evangelical churches. But I was most intrigued by the way the spirits of ancestors can possess practitioners during the rituals, and in the poem I wanted to enter, in my imagination, into the inner beings of practitioners transformed by the visiting spirits of ancestors. The poem began to stir in my imagination when I read this marvelous and mysterious declaration in Taylor’s manuscript: “The eguns are more likely to be found / entangled in the roots of trees.” Though I don’t use this as an epigraph, I begin with the ghostly speakers untangling themselves at dusk from the aerial roots of banyan-like gameleira trees. They go forth into the evening along the shores of a setting very much like Sacatar and Itaparica, transformed into ancestral spirits.

Read the rest in Part 2:

"Morning Writer" and Language as the Carrier and Transmitter for Human Culture

The Missouri Review: Can you describe your writing practice? You are such a prolific poet, and I’m curious to hear what your writing practice looks like on a day-to-day basis. Relatedly, how has your writing practice evolved over time? Carolyne Wright: