"Morning Writer" and Language as the Carrier and Transmitter for Human Culture

Part 2 of our Interview with Carolyne Wright

The Missouri Review: Can you describe your writing practice? You are such a prolific poet, and I’m curious to hear what your writing practice looks like on a day-to-day basis. Relatedly, how has your writing practice evolved over time?

Carolyne Wright: Thanks for the kind words about my being prolific! On a day-to-day basis, watching how I spend the hours in any given day, I don’t feel so prolific, but I do try to practice “Not a day without a line,” that old adage attributed to any number of writers and artists. I admire the novelists and nonfiction writers who sit down at dawn and write till noon, for example; or a writer like Isabel Allende who starts every new book on January 8th and writes for several hours a day till she finishes. I don’t have a fixed writing schedule, but I do tend to settle down and write more at night, after daily tasks and get-togethers are done, classes and workshops are over, banks and offices are closed and phones don’t ring. Rita Dove has said that she often writes all night till dawn, then sleeps. I sometimes joke that I am a morning writer—I write from midnight till 4 a.m. I tend to stop before dawn, though, because if I hear birds singing and see the sky lightening, then it’s harder to finally go to sleep!

I regard all writerly acts as part of the practice: whether it’s waking up from sleep with lines running through my head, or overhearing some scrap of conversation on the radio or on the metro, or reading some work that calls up new lines or phrases—I have to scrawl such gift lines by hand in my journal. Likewise first typing out a handwritten draft of a poem, or revising a prose piece or poem already in typescript, or organizing a manuscript in progress—moving poems or essays around to see how they “speak” to each other in sequence—or editing galleys of poems or prose pieces forthcoming in journals, or even typing out replies to these questions: it’s all part of the process. If I feel the need to write but can’t think of anything new, or no revision in process calls out for another pass, I go back through some of my journal pages (all organized by year, in banker’s-style storage boxes), look at handwritten first drafts (marked with post-it notes for easier discovery) till one of them stands out, and I copy those lines by hand onto scrap paper, making changes and additions as I go. After writing a poem out by hand at least once, then perhaps revising by hand a second or third time, I type it into a Word file, to see approximately what it looks like on a printed page. (Prose I tend to type directly into a digital file, but poetry almost always wants to begin by hand.) Some form of writing is always in progress. Actually, I have worked pretty much like this since graduate school—I set a “derriere-in-chair” schedule only if I have a hard deadline to meet, and that is usually for the few days till I meet that deadline. Thanks for this question, by the way—it has inspired some thought about my practice. And the “derriere-in-chair” quip came to me just now, as I was writing this!

[I]t has been important for me to have a poem take place (great phrase, no?) in a real location, and to give my “airy nothings” of thought and memory and imagination and emotional dynamics between the speaker and other characters in the poem what Shakespeare called “a local habitation and a name.”

TMR: Reading through some of your poems, I was struck by the varied ways that place figures into your work: abstractly, temporally, culturally, and geographically. Could you describe how you think about place when you’re drafting a poem?

CW: For my 16th birthday, I think it was, my mother, who had noticed my growing interest in poetry, presented me with a copy of Five Poets of the Pacific Northwest, edited by Robin Skelton, which featured work by Kenneth O. Hanson, Richard Hugo, Carolyn Kizer, William Stafford and David Wagoner. These poets of what was called the “Northwest” school, also including Theodore Roethke and Madeline DeFrees, were my earliest influences. All of them located their work very deeply in place—that place being the lush, temperate rainforest, the mountains and islands and inland waterways of Western Washington state; and also the regions east of the Cascade Mountains, the “Inland Northwest” of rolling wheat lands, steppes, foothills and deserts bisected by the Columbia and Snake Rivers, and the human lives that played out in these regions. I resonated with the sensibilities of these poets and the landscapes of their poems—indeed, in their poems they taught me how to look at the landscape, how to internalize it, take it in to a poem. Later, I was fortunate to study with some of these poets at conferences (DeFrees, Hugo, Kizer, Stafford) and be associated as a colleague with David Wagoner, and as a poet friend with DeFrees. Ever since it has been important for me to have a poem take place (great phrase, no?) in a real location, and to give my “airy nothings” of thought and memory and imagination and emotional dynamics between the speaker and other characters in the poem what Shakespeare called “a local habitation and a name.” The place is not just literal, though—in a wonderful way the setting of the poem also becomes representative of those thoughts, feelings, and psychic dynamics between characters.

One critic, who honored me by calling me a “trustworthy naturalist, whose language of description, even when it is most figurative, has the ring and weight of fact,” also stated that the natural settings in my poems “figure situations in which gestures of the mind and elections of feelings. . . . map and re-map the inner life of ongoing relations with others and with oneself.” (Thank you, Donald Dike, for that most generous introduction to my first book, Stealing the Children!). And this habit of mind in the making of poems has traveled with me over continents and through countries, and into the human history and cultures that overlay and exist amidst the natural environment. At Sacatar, for example, I found in the library a copy of Aves do Brasil and one other big, National Geographic-style, Portuguese-language guide to the birds of Brazil, and left them on a table in the dining room. In this way, when birds flitted by, or perched outside the windows (always open in the day, no window glass in this tropical region), or even flew into the rooms (!), I could look them up. Pretty soon, the other resident fellows were consulting these books as well! It’s important to me to give correct specific names to the birds and other creatures, so wherever I go, I try to learn the local birds and animals, tree and plant species, rock formations and soils, and the human settlements as well—to honor these local habitations and inhabitants with their real names. And as much as possible, I try to learn the human languages as well—the languages carry and transmit the local human culture!

[H]uman languages carry and transmit human culture, and translation is one form of carrying over the cultures and history embodied in languages. For me, the closest of all possible readings of poetry from another language is the practice of translating that poetry. I have learned a great deal about my own first language by trying to render another language’s poetry into English as fluent and graceful as if the poems had been originally written in English.

TMR: In addition to being an acclaimed writer, you’re also an award-winning translator. Can you describe how your work as a translator informs your work as a poet and vice versa?

CW: As I wrote at the end of the previous response, human languages carry and transmit human culture, and translation is one form of carrying over the cultures and history embodied in languages. For me, the closest of all possible readings of poetry from another language is the practice of translating that poetry. I have learned a great deal about my own first language by trying to render another language’s poetry into English as fluent and graceful as if the poems had been originally written in English. I have always been drawn to learning languages—not lots of languages, but a few languages as deeply as I am able to enter into them. I began with Spanish, which I had studied for half a dozen years in school and then was fully immersed in for a year while in Chile on a Fulbright-Hayes Study Grant during the presidency of Salvador Allende. There I interacted pretty much only with Chileans and so became, as was my goal, as close to bilingual in Chilean Spanish as possible. I wrote a series of poems and essays about that time, and also sought Chilean poets to translate. Pablo Neruda had recently won the Nobel Prize in Literature, so there would be guaranteed interest in translations of his work, but Neruda already had a small army of established translators.

So I decided to focus on Jorge Teillier—like Neruda from the rainy South of Chile, but a generation younger, and whose work I first encountered in the bookstore of the Universidad de Chile in Santiago. Teillier had a substantial reputation in Chile, but he was not well represented in English translation. His free-verse style and diction were contemporary and compatible with my own. The dreamlike, small-town, rainy ambience of Teillier’s poems appealed to me, a young poet from Seattle whose earliest contemporary poetic influences were the poets of the Northwest School I named earlier. My travels to the South of Chile, regions similar in geography, vegetation, and atmosphere to my native Pacific Northwest, made elements of Teillier’s poetic world feel very familiar. I never met Teillier, but we did correspond (by typed and handwritten letters!), enough for me to receive from him the permission to translate and publish his work, and to get answers to a few questions I had about passages in his poems. In Order to Talk with the Dead, a bilingual volume representing the entirety of his poetic career, was published by the University of Texas Press, and received the National Translation Award from ALTA, the American Literary Translators Association.

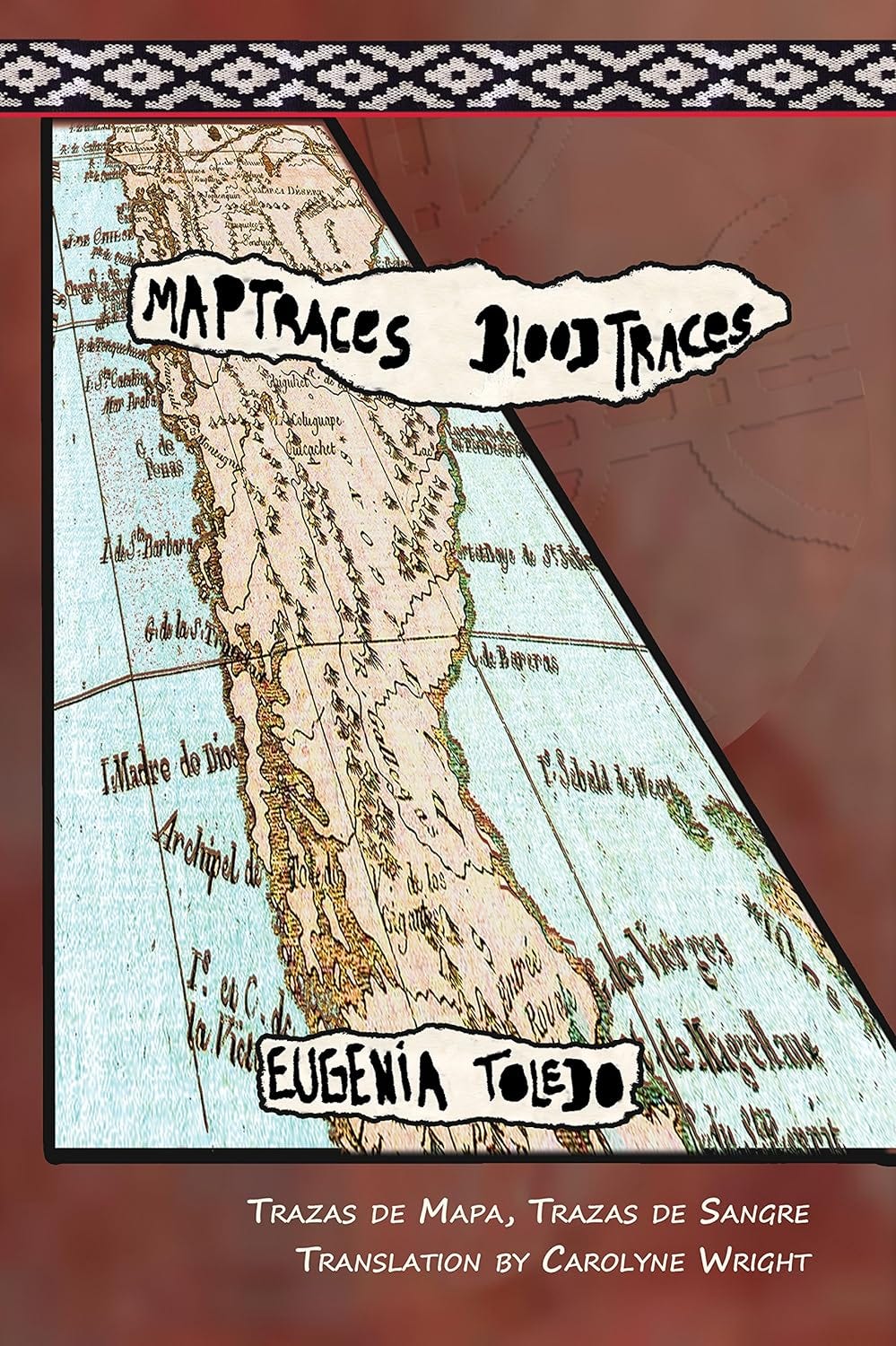

Years later, in Seattle, I met Eugenia Toledo, also from the South of Chile—in fact, from Temuco, Neruda’s hometown!—she had come to Seattle in 1975 to pursue a doctorate in Latin American literature, having lost her university teaching job in Temuco after the military coup. Eugenia visited a class of mine on Latin American poets at Hugo House, and she regaled us with anecdotes about some of the poets we were reading—she had known many of them! Meeting Eugenia was a real gift: we had Chilean poets and Chile itself in common! We hit it off and began to work together, translating each other’s poetry, team-teaching courses on Neruda and other poets at Hugo House and elsewhere, and having long talks, mainly in Spanish, about poets, poetry, politics and more. With support from Washington State – Chile Partners of the Americas, we traveled throughout Chile for a month in 2008, giving talks and readings in schools and universities and cultural centers from La Serena in the North to Valdivia in the South, visiting sites of literary moment and meeting fellow writers and poets. On this journey, I watched Eugenia re-connect with her past, including colleagues and friends she had not seen since before the military coup. There were emotional reunions with colleagues who had been exiled to different countries for decades before returning to Chile after the restoration of democracy. From this journey of re-encounter emerged the bilingual sequence of poems, Trazas de mapa, trazas de sangre / Map Traces, Blood Traces (Mayapple Press, 2017), featuring Eugenia’s poems in my translation, with notes from both poet and translator. This book was a Finalist for the 2018 Washington State Book Award in Poetry, and also for the 2018 PEN Los Angeles Award in Translation.

During that Fulbright year in Chile, I also crossed the continent to Brasil—to Salvador, Bahia, where I spent several weeks before, during and after Carnaval. I fell in love with the Brazilian people, their culture and language (which I was able to pick up more or less because of its many cognates and similarities with Spanish). For years afterward I longed to interact more fully with Brazil. That opportunity came in 2011 when I discovered Zumba and Afro-Brasilian dance, taught by Daniel Santos, from Salvador, Bahia, and his American wife Aileen—they are wonderfully dedicated teachers and creators of community through dance, capoeira and performances of their company, Bahia in Motion. Soon thereafter, I learned that I could take courses on a non-credit basis at the University of Washington for a nominal enrollment fee (our tax dollars at work at land-grant universities!), so for several years I took the whole sequence of Portuguese language and literature courses, and was fairly fluent by the time I returned to Bahia for the Sacatar residency in 2018. Curiously, with Portuguese, I have been translating work by a few Brazilian poets and writers—Alex Simões, Márcia Tiburi, and Leonardo Tonus: Alex I met via Sacatar in 2018; I met Márcia and Leo when they visited the University of Washington in spring 2019 for the Primavera Literária Brasileira, a project to bring Brazilian writers and poets to universities and cultural centers throughout Europe and the U.S. So far, these translations of poems and fiction pieces have appeared in journals like Channel Magazine, The Common, The Kenyon Review, Nimrod International Journal, PRISM International, and Tupelo Quarterly.

Then there is the huge and still ongoing project of translation of the work of Bengali women poets and writers! I lived in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), India, for nearly two years on an Indo-U.S. Subcommission Fellowship for Advanced Research; and then for nearly two years in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on a Fulbright Senior Research Fellowship, to collect and translate, with the assistance of Bengali collaborators, the work of Bengali women poets and writers. An anthology of this work is in progress, entitled A Bouquet of Roses on the Burning Ground: Poetry of Bengali Women. So far, three volumes of poetry in my translation by Bengali women have been published: The Game in Reverse: Poems by Taslima Nasrin (George Braziller, Inc., 1995); Another Spring, Darkness: Selected Poems of Anuradha Mahapatra (Calyx Books, 1996); and the anthology of poems edited, and with my critical introduction, Majestic Nights: Love Poems of Bengali Women (White Pine Press, 2008). These translations have appeared in dozens of literary magazines, anthologies, and journal features, as well as in textbooks from Bedford / St. Martin’s Press, Macmillan, W.W. Norton & Co., Penguin, and Vintage/Random House, among others.

In Dhaka, Bangladesh, in late 1989, I met English Poet Laureate, Ted Hughes, the guest of honor for a national poetry festival sponsored by the Bangladesh government. Conversations with him, particularly one in which he spoke at length about his life with Sylvia Plath, inspired reviews, essays and poems, as well as occasional correspondence with Hughes, and with his widow after his death in 1998. (Much of this correspondence is preserved with Hughes’s papers, which are housed at the Emory University Library.) This encounter, as recounted in my memoir essay, “What Happens in the Heart: A Conversation with Ted Hughes” (originally published in the Poetry Review, U.K.), has been cited in subsequent biographies of Ted Hughes, including Ted Hughes: The Life of a Poet by Elaine Feinstein (W.W. Norton, 2001); and Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life, by Sir Jonathan Bate (William Collins/Harper, 2015).

In early 1990 in Dhaka, I met and began working with dissident Bangladeshi poet and writer Taslima Nasrin, to produce the first translations of her work into any other language. In 1993 and 1994, when fundamentalist death threats brought Nasrin’s case to international attention, I was instrumental in making my translations of her work available for the human-rights campaign on her behalf. These translations were published in The Game in Reverse, and in anthologies such as The Vintage Book of Contemporary World Poetry, ed. J. D. McClatchy (Vintage / Random House, 1996); Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from Asia, the Middle East & Beyond, ed. Tina Chang, Nathalie Handal, Ravi Shankar (W.W. Norton & Co., 2008); and Poetry 180: A Turning Back to Poetry, ed. Billy Collins (Random House, 2003), though translator credit was not given in this last instance. In addition, I was approached by jazz saxophonist and composer Steve Lacy, to provide my translations to English for The Cry, a “jam opera” / concert / CD featuring the poetry of Taslima Nasrin, set to Lacy’s music and sung by Irene Aebi.

For these translations, I have received a Witter Bynner Foundation Grant in Poetry and an NEA Grant in Translation. In addition, I was a Fellow of the Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College, and held research appointments with the Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies at Harvard University, the Wellesley College Center for Research on Women, and the Asian Studies Program at Emory University. For the past several years, my translation focus has been on Eugenia Toledo (Chilean Spanish) and on Brazilian Portuguese; but I have several more volumes in translation from Bengali to complete and get published! All in due course!

TMR: What are you working on now, and what are you reading right now?

CW: I have a few projects underway—besides the translations of Bengali women and Brazilian poets and writers that I describe just above, I am working on other poems for the Bahia series; also poems for a memoir in poetry that moves through childhood, adolescence and beyond, to confrontations with mortality via caregiving of ailing family members—this one is tentatively entitled Mother-of-Pearl Women; also a book of essays, interviews and reviews that was invited for one of the University of Michigan series of poets on poetry. Last year I put together a tentative TOC, which involved researching some of the internet-only and print format-only book reviews, interviews, and essays . . and a few for which I have no electronic copies so will have to type, 1950’s-secretary style, from original typescripts or original print journal copies, into Word files. This volume has a fun working title: Confessions of a Nonce Formalist. And it is fun and illuminating to revisit all these pieces I have written over the years. And I’m also still giving readings and interviews, and teaching courses on poetry and memoir, based on my most recent book, Masquerade: a Memoir in Poetry (Lost Horse Press, 2021).

I’m always reading several books of poetry at once—new and recent books, as well as older ones from among my alphabetically arranged poetry shelves, books that I dip into over and over. Kelli Russell Agodon’s Dialogues with Rising Tides; B. H. Fairchild’s The Art of the Lathe; Ada Limón’s The Carrying; the late Lynda Hull’s Collected Poems; Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets for My Once and Future Assassin; volumes in the U of Michigan Poets on Poetry Series by Tess Gallagher (A Concert of Tenses) and Yusef Komunyakaa (Blue Notes); two books in the Lost Horse Press Contemporary Ukrainian Poetry Series: Apricots of Donbas, by Lyuba Yakimchuk (translated by Oksana Maksymchuk, Max Rosochinsky, and Svetlana Lavochkina) and Eccentric Days of Hope and Sorrow, by Natalka Biloserkivets (translated by Ali Kinsella and Dzvinia Orlowsky); the Portuguese pages of the bilingual Poemas do Brasil of Elizabeth Bishop, also Poemas escolhidos de Elizabeth Bishop, both volumes translated by Paulo Henriques Britto, regarded as the best translator to Portuguese of her work. It is fascinating to read in Portuguese this poet whose work I know so well in the original. . . . and to read the facing pages in English so that I can check on Britto’s translation choices!

And every night before sleep, as I have done since I was in Salvador, Bahia, in June and July 2022—the first segment of my 2022-2023 Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award—I read a few more pages of Minha vida de menina, the diary-format narrative written from 1893–1895 by “Helena Morley,” the nom de plume of Alice Dayrell (1880-1970) , a girl of English and Brasilian heritage growing up in the small city of Diamantina in the final two decades of the 19th century. Years ago, when I worked in a bookstore in New Orleans, I had read Elizabeth Bishop’s translation of this classic, The Diary of Helena Morley, and had always hoped to learn Portuguese well enough to read it in the original. Minha vida de menina has had the same degree of influence in Brasil as another Diary of a Young Girl has had world-wide; but unlike Anna Frank’s “forced maturity and closed atmosphere,” as Miss Bishop puts it in her introduction to The Diary of Helena Morley., Alice Dayrell captures “authentic childlikeness . . . classical sunlight and simplicity” in her diary.

I try to be in process of reading a book in Portuguese all the time, likewise a book in Spanish: poems of Neruda in the original—despite his repellent treatment of women at various times in his life, the linguistic energy and boundless fonts of rich imagery in his poetry, especially in works like Residencia en la tierra and Canto General, still inspire. And I am reading another volume of Eugenia Toledo’s poetry, her Casa de máquinas, about her growing up in Pueblo Nuevo, Temuco, where her father, don Eugenio Toledo, a pyrometallurgist who worked with high-temperature metals, operated a small foundry that crafted specialized tools and machinery parts. The family home was in the same compound, so Eugenia grew up observing her father’s work up close.

TMR: Do you have any advice for writers who are early in their publishing careers?

CW: Read widely and voraciously: poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction—more widely in your major genre—learn about the major figures in your genre, as well as up-and-coming voices.Also read works of science and history and biography and fine arts and music—at least articles on these topics in magazines and online. Read literary journals, both print and online journals, to get a sense of who is out there, publishing in these magazines—writers and poets of older (and younger) generations as well as of your own—read to discover what kind of work each journal likes, the wide range of editorial sensibilities out there. Also, make sure to be able to afford to subscribe to a few journals, to support the magazines you hope will support you via publication. Many literary contests include a year’s subscription to the journal sponsoring the contest; or if the subscription is an added option, take it, especially if it’s discounted! I tend to do such subscriptions tied to contests; I don’t always renew, but I do get a good idea of each journal by reading the issues sent to me during that year or two.

A good place to start for a directory of literary journals is the Poets & Writers Directory of Literary Magazines and Journals. Find that directory under the Publish Your Writing tab, along with loads of other invaluable information under other tabs. If you have attended an MFA or other Creative Writing program, you may already be familiar with the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, along with its website which has valuable information about publication, writers conferences and literary centers, writing fellowships, contests, and other opportunities. And both of these organizations publish bi-monthly magazines. As an AWP member, I receive the AWP Writers Chronicle (which went to online-only format as of last year); and I have subscribed to Poets & Writers since I was a grad student in Creative Writing at Syracuse. P & W is still in print format, and you can also buy it on magazine stands, especially at independent and university-affiliated bookstores.

Write every day, revise a piece in progress if nothing new comes to you, write prose if no poetry comes, or (if you’re a prose writer) poetry if no prose comes. Keep a journal of notes and images and possible titles, also dreams and narratives of interesting interactions you observe or take part in, reconstructed dialogue, whatever. This will be your source material, a sort of hopper, as one artist friend calls it, to draw from. Keep the journal (or a few blank pages from it) with you at all times, so you can note down any line that comes, and not forget it. Who cares if people think you’re obsessive! Or you can write lines on your cellphone or tablet—though I personally would find using such devices unwieldy and intrusive. Learn to be unobtrusive and matter-of-fact about making notes, and other people finally won’t even notice. Your writing is an integral part of your life, and with low-tech devices like paper and pen, you can write anywhere, anytime.