OCD and Me: A Conversation with Cynthia Marie Hoffman

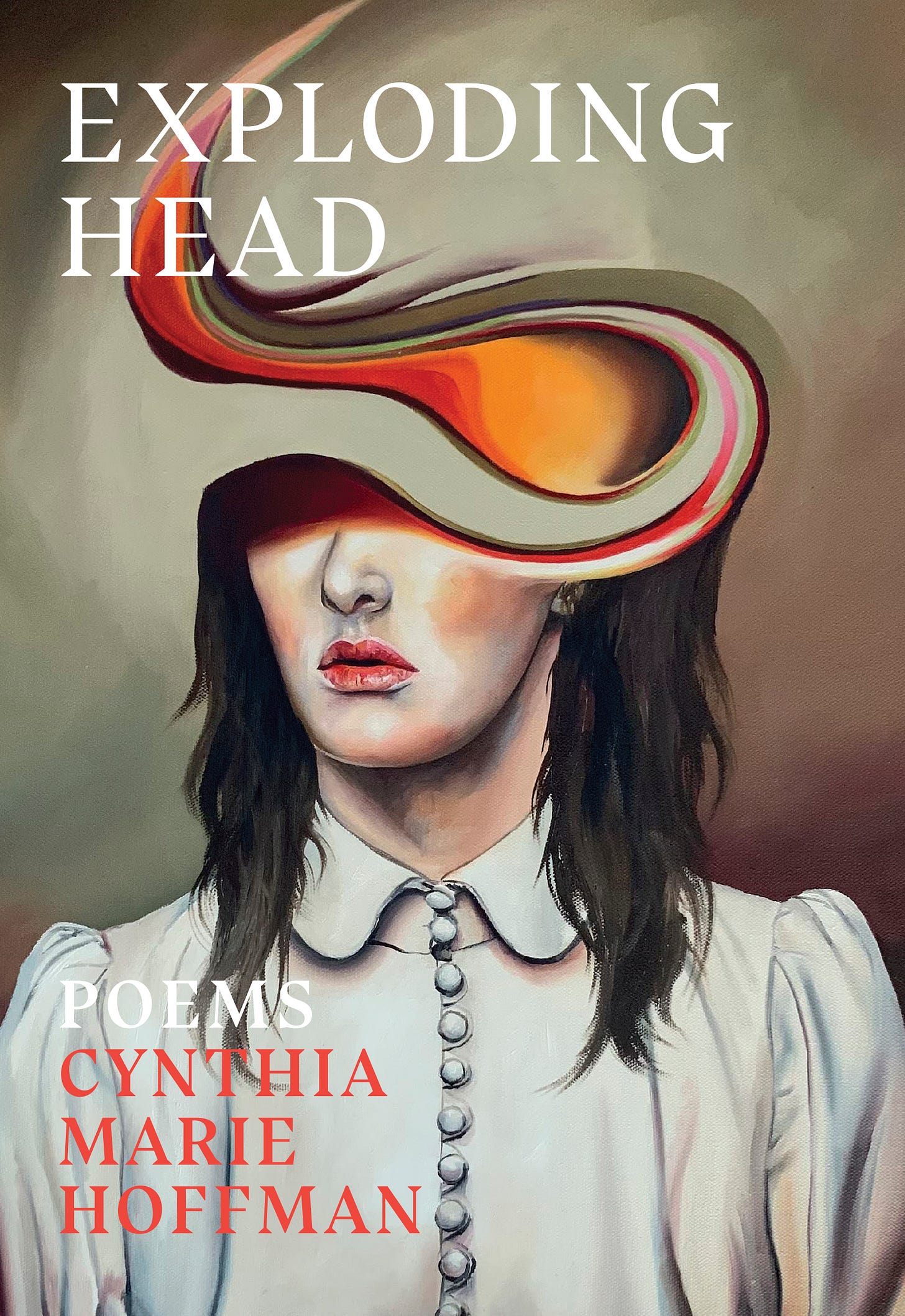

In which TMR catches up with former contributor Cynthia Marie Hoffman, whose new book EXPLODING HEAD is out now.

In this interview, Missouri Review intern Sarah Molitor talks with Cynthia Marie Hoffman (featured in 46.2 (Summer 2023) and a former Poem of the Week contributor) about her new book, Exploding Head, published earlier this year by Persea Press, as well as her evolving relationship to being OCD and branching out into other creative genres.

Sarah Molitor: How would you describe your writing?

Cynthia Marie Hoffman: With the publication of my most recent collection of prose poems, Exploding Head, I’ve heard readers describe my work as primarily surreal, strange, and lyric. Exploding Head inhabits the world of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), which interrupts reality with vividly imagined—and often terrifying—events. Dead women wander through the kitchen, “clanging into each other like windchimes.” A lake swallows a cloud. My poem Receiving Angel, published in The Missouri Review, features an angel whose arms are so long you can lay across them “the skyscraper you fall from every night.”

The poems in Exploding Head feel surreal because they work to recreate the lived experience of intrusive thoughts. But all my work could probably be described as image-based and a bit strange. But I sometimes forget, because when I’m drafting the poems, imagery and strangeness arrive on the page so naturally that they seem not to announce their presence to me at all.

Accessibility, clarity of communication, and argument-based structure are what first come to mind when I think of describing my own writing, perhaps because these are the most hard-won aspects of craft that demand most of my attention. I truly labored to weave all that strange imagery together and make some sense of it, you know? But how would a reader know that? Good writers (not that I claim to be “good”—that’s for someone else to decide) make it look easy. When you’re the writer, it’s hard to see the forest for the trees—the poem I wrote rather than the process by which it was written. But we hope the opposite is true for readers; in fact, if the craft is highly visible to the reader, it’s a distraction. You shouldn’t see that glob of hot glue holding up the hem.

I’m honored when readers say they “devoured” Exploding Head in one swift sitting. I hope it means I did my job in making the book read like an accessible, page-turning memoir. But I’m also honored when readers say they read it slowly, needing to savor the language and imagery. I hope it means I made something strange and beautiful.

SM: OCD is in the forefront of your latest book ‘Exploding Head.’ What made you want to write about OCD? Was mental health awareness or representation in the back of your mind?

CMH: I’ve lived with OCD my entire life, but because most of my obsessions and compulsions are performed mentally (such as ruminating and counting) rather than physically (such as checking locks), for better or worse, I slipped through childhood and most of my adult life undetected. It meant that if I didn’t want to share my diagnosis, I didn’t have to. And I didn’t want to.

Shame, as well as a fear of being misunderstood, kept me from talking about what was going on in my mind. But eventually, the isolation and secrecy took its toll, so that by my late 30s, when I started writing these poems, it was becoming impossible for me to continue not talking about OCD. The page was a realm I could control, where I could share my story bit by bit, poem by poem, as I discovered a language for speaking about the disorder for the first time.

Mental health awareness and representation were nowhere in my mind. I was so consumed by just finding the words to tell my own story that I couldn’t yet envision how publishing a book about OCD would be received by readers or how it might be positioned as OCD awareness advocacy. In fact, I had been so isolated for so many years, trying to manage my symptoms on my own, that I wasn’t aware of OCD-related resources that could have been helpful to me, let alone could I begin to imagine my book as a resource that might be helpful to others.

I didn’t even say “OCD” in any of the poems themselves. That’s how little practice I had talking openly about my diagnosis. It wasn’t until I started working through the back cover copy with my publisher that I heartily committed to naming obsessive-compulsive disorder in Exploding Head’s description and marketing materials. The more poems I’d published in journals, the more acutely I’d become of aware of just how misunderstood OCD is in popular culture. I’d thought what was going on in my poems was so obviously OCD that I wouldn’t have to name it. For example, repeatedly visualizing myself being shot is obviously OCD. Feeling unsure about whether I’ve run over someone with my car is obviously OCD. Seeing an angel in my bedroom at night who will whisper the secret of heaven in my ear if I don’t keep counting the four edges of the window in a pattern that draws a “4”; obviously, that’s OCD. Right?

Wrong. I was surprised to learn from some readers that they had not realized my poems were about OCD. That’s when I realized that my not speaking openly about it wasn’t helping and that in fact, I had a responsibility to contribute to OCD awareness. That meant I had to become aware of available resources, learn the proper language, study up on my OCD facts. I consider writing the book and doing OCD advocacy work to be two related but very separate efforts.

Poetry isn’t therapy. But writing Exploding Head and connecting with readers has changed my life. I feel much less alone. I hope it has made readers feel less alone, too.

SM: What was it like having your work in TIME?

CMH: It was a dream, certainly, in my first year of writing essays, to secure a byline like TIME. It meant that my words would find a wider and very different type of readership than my poems ever could. The topic of the essay, OCD and America’s gun violence problem, was perhaps more important to me personally than anything else I’d written, so I hoped (and still hope) the essay would find the readers who need it.

Of course, the exposure meant I was newly vulnerable to the potential trolling of internet strangers, especially when the magazine shared a quote from my essay on their main Instagram page. I tried to heed the general advice not to read social media comments, but this was my actual first rodeo, and I was curious—perhaps less about the comments themselves than about how I would handle reading them. But I surprised myself. I felt relatively unmoved by the words of those who disagree with me about gun violence or misunderstand OCD. More importantly, I was greatly moved by words of thanks offered in solidarity from others who believe in gun control, who have OCD themselves, or who love someone diagnosed with OCD. I’m glad I braved the comments section so I could receive those.

It was also my first rodeo working with an editor who would pull my lyric, poetic prose toward a magazine’s “house” style. The editor I worked with, Rachel Sonis, did a fantastic job of peeling it back in manageable, onion-thin layers. Each edit, I was encouraged to let go of a few more “darlings”—images that were presented without explanation, quiet metaphors. Through several rounds of edits, I understood that we were uncovering a core of directness and clarity the very likes of which I had been trained, as a poet, to veil.

It was an incredible learning opportunity. I walked away with a greater understanding of various types of readerships and a sharpened ability to interrogate moments in which I might be falling victim to an overreliance on vague suggestions rather than bravely stating the explicit argument outright. Yes, in my essays. But also, yes, even in my poetry.

SM: What has been your proudest moment in your career?

CMH: Writing the personal essay “The Beast in Your Head” and seeing it published in The Sun.

In early 2023, I set a goal to write essays. I hadn’t written a personal essay since undergrad (which was, gulp!, decades ago), and I was nervous about experimenting with a “new” genre. Of course, I’d decided I had to be perfect at it on the first try—and if you’ve ever felt that way, you know it really kills the vibe. I had a list of essays I would write, if only I could start.

I had the chance to sit down with two accomplished multi-genre writers, Jesse Lee Kercheval and Judy Mitchell, at a local coffee shop. I’d locked myself in as a poet for so many years, and I thought maybe they had the key to throw the gates wide open. I brought my notebook and a printout of the Excel spreadsheet where I’d been plotting (i.e., procrastinating) my two-dozen essay ideas that I “can’t write”! I must have looked as frazzled as I felt, but they assured me every writer feels this way—even they had felt this way moving between genres. The key was that there was no key—just the page. The wise words they had to offer were simply, “you can do it.” But there’s no understating how powerful that was to hear. We were reminded that writers supporting other writers often just looks like giving each other permission when we struggle to give it to ourselves.

I went home and got to work on the first essay idea that was truly burning a hole in my brain. “The Beast in Your Head” delves into OCD more deeply than I could in the poems in Exploding Head because the essay form is so expansive by comparison. Whereas the prose poem had felt like a solid brick on the page, the essay was a lung breathing. And for the first time, I was writing about music and joy, subjects that felt unfamiliar and invigorating. For a good six months, I lived in the world of that essay, figuring things out as I was driving, staying up late into the night listening to Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” on repeat.

The Sun happened to post a call for personal essays about music, and that’s when I fantasized that I’d not only actually finish this darn thing but that I’d publish it in The Sun, a dream mag with a wide readership and home to some of the most beautiful and memorable personal essays I’d read. And that’s exactly what happened.

But this was not my proudest moment just because of the publication; it was more about the experience of writing. I wrote a half dozen essays that first year. I was proud of myself. Some were published in great outlets, and some fell apart at the draft stage or became hopelessly tangled—but each attempt was an act of fiercely, stubbornly picking the lock of my own self-limiting beliefs.

Once I was free, those limitations seemed so dumb! I experienced a period of what I could only call mourning for what I perceived as decades of lost creativity. During all the years I’d been writing poems (or not writing anything), I’d also had ideas for short stories, novels, and essays, but I’d brushed them off because I thought I had to pick a lane, and my lane was poetry. I’m still moving through that regret.

If anyone reading this is feeling stuck and needs to hear this: I give you permission. You can do it.

SM: What does the writing process look like for you?

CMH: I make writing harder than it needs to be by self-imposing big expectations and grandiose ideas. I don’t recommend my process. But it comes from a genuine obsession with and curiosity about books. I’m fired up by how poems speak to each other. Even though I write one poem at a time, I write each poem toward how I envision it clicking into place in the final book. This means my poetry books are less “collections” (poems gathered together after a period of writing) than they are “projects” (poems written intentionally toward a preconceived theme or constraint)—a book of travel poems (Sightseer), poems about birth and superstition in early medicine (Paper Doll Fetus), a collaged journey of genealogical research (Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones), a memoir in prose poems about OCD (Exploding Head).

Writing toward the book gives me a sense of purpose, and I thrive in environments that stimulate obsessive, deep focus. Whenever I’m deep into a project, I’m never starting a poem from absolute scratch. Each day I return to the writing desk, I’m returning to the book I’m working on.

This process has its drawbacks. I’m like a horse pulling my carriage down a busy street with blinders on, blocking out anything that isn’t visible straight ahead on my singular, predetermined path. Might there be some gorgeous sunflowers for sale on this street corner? Certainly! But I’m not writing a book about sunflowers!

But, at its core, writing is a form of paying attention, and in order to look at one thing, we must look away from another. Writers are repeatedly called to make that choice. Sometimes I regret having chosen too narrowly.

SM: If you’re able to tell us, what are you working on currently? Any new projects?

CMH: For the first time, I’m writing poems that aren’t part of a preconceived project. I have no idea what the next book will be about or whether the poems will become a book at all. This isn’t an experiment I put upon myself on purpose, but I’m gritting my teeth as I move through it, nonetheless, trying to remain open to whatever lesson the experience has to teach me.

It just so happened that once I’d finished Exploding Head, I didn’t have another project idea ready to go, but I continue to be very active with poetry groups and creative peers with whom I share work. Looming deadlines mean I’ve been writing random poems about whatever. Over time, I’ve amassed a good 50 pages worth of revised and polished “random poems about whatever.” I keep thinking I just have to keep the writing muscle warm until the next book idea strikes, and then I’ll be ready to start writing. But what if I’ve been writing the next book all along?

With fewer self-imposed constraints, I’m finally free to engage with any idea that occurs to me, rather than saying “no” to ideas because they don’t fit the project. That’s a freedom I haven’t allowed myself in 25 years. But so much freedom has been unsettling. I’m not used to facing so much uncertainty on the blank page.

In the end, I know a collection of seemingly random poems will cohere simply because I wrote them, and I know I’m subconsciously exploring recurring themes simply because I’m a person moving through the world with the ideas and obsessions that make me me. I’ve taken some time to review what I’ve written so far by interrogating the themes that have cropped up (I love a Table of Contents color-coded by theme) and running the manuscript through a word frequency counter. Turns out, I’m currently obsessed with climate change, parenting, and friendship in midlife. It’s not a project, but perhaps it will be a collection.

I’ve also been writing more essays, which doesn’t come with the same pressure of book-making for me. Maybe because I’ve never written a book of essays before. There is so much more I want to write about OCD than I could put in the poems. I’m not done yet.