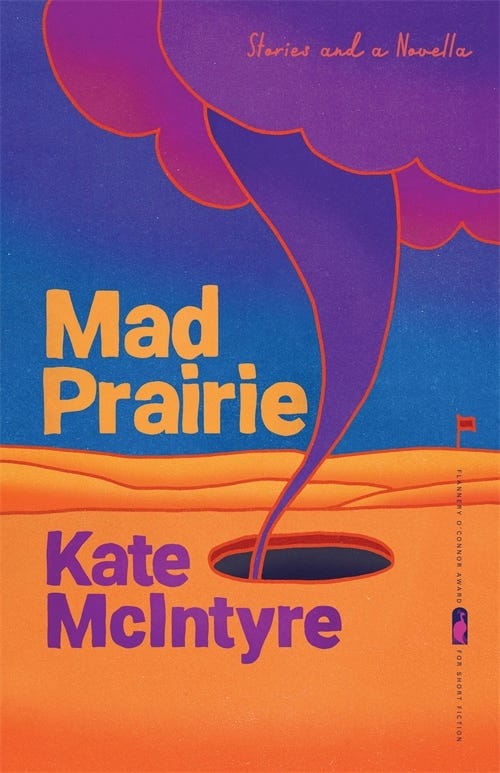

Kate McIntyre, zozobra, and "smart, weird Midwesterners" in Mad Prairie

by Aidan Koch and Audrey Dae Bush

In this interview, we catch up with a former managing editor Kate McIntyre, whose debut collection Mad Prairie won the Flannery O’Connor Prize for Short Fiction. Currently, she is an assistant professor of creative writing at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and lives in Worcester, Massachusetts.

How would you describe yourself?

Five foot four(ish), blonde(ish), forty(ish), writer of fiction and creative nonfiction (katemcintyrewriting.com), coeditor of a flash speculative literary journal (hexliteary.com).

And what about your writing?

I came across a term in Naomi Klein’s excellent new book, Doppelgänger, that gets at a quality I always chase in my prose, for which I’d never had language: zozobra. Klein learned the term from the philosopher Emilio Uranga. She unpacks the meaning, quoting Uranga, here: “[Zozobra is] generalized wobbliness: ‘a mode of being that incessantly oscillates between two possibilities, between two affects, without knowing which one of those to depend on’—absurdity and gravity, danger and safety, death and life. Uranga writes, ‘In this to and fro the soul suffers, it feels torn and wounded.’”

I’m also forever interested in the workings of power—how characters seize and hold it, how they exert their will, how injustices and power vacuums in nations and states get reflected at the micro level, in personal relationships.

What’s your creative process like?

Long and slow. I taught from a wonderful new craft book this term, How We Do It: Black Writers on Craft, Practice, and Skill, edited by Jericho Brown, and in one essay, Charles Johnson shares an anecdote from his teacher John Gardner. A reader meets Gardner and tells him she likes his work much more than she likes him as a person. Gardner points out that of course a reader likes his work best because all the best bits of himself, over time, have made it. This resonates with me, this buildup of fine detail that results in a text that you never could have fathomed when you first begun a draft.

Why fiction, in particular?

I have Midwestern distaste for discussion of the self, for putting the self forward. Fiction allows you to affix false glasses and a mustache to the self.

Describe what you did at the Missouri Review.

I started at TMR in the internship in publishing class. From there, I took over as contest editor, and then as anthology editor. After I got my PhD, I served for two years as managing editor.

As I tell my students, the single best education for a serious young writer is reading submissions at a literary journal. You figure out very quickly why some submissions work and others don’t, and you gain a perspective on what is getting written right now, in this moment. You can use this knowledge to figure out what makes your own work singular, and you can lean into these aspects as you cultivate your voice, your aesthetic.

What did you learn while serving as an editor?

Well, I learned how to run a literary magazine. Along with my co-editors Danny Miller and Joe Aguilar, who are also TMR alums, I cofounded the flash speculative literary journal hex (hexliterary.com). In our two years of existence, we’ve published extraordinary work by 100 authors, garnered major reprints (Best Small Fictions, Best Microfiction, a forthcoming Bloomsbury speculative fiction text), and taught fifty students about literary magazine editing through a course at WPI based on TMR’s internship.

At TMR, I also figured out how to explain the importance and vitality of literary magazines to people from outside our world. It’s a case that must get made over and over again, and the more people who are equipped and motivated to speak up for magazines, the better.

When you evaluated fiction, what elements did you look for in submissions?

I looked for stories that weren’t just about capturing a single character’s emotional landscape, but instead, pieces where a writer engaged with social, cultural and political movements in world, where the gaze was both inward and outward. I also loved humor.

Can you recall any TMR submission you particularly liked that was eventually published?

I teach a travel writing class at my current institution, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and each year I assign Elizabeth Lindsey Rogers’s essay “One Person Means Alone.” It’s a depiction of cultural difference, centered on a public swimming pool in China. She uses the pool as a mechanism to explore varying meanings of privacy, of belonging and comfort, and of being a good community member. I was also a first reader on C. Pam Zhang’s amazing story “And How Much of These Hills Are Gold,” which came to us as a contest submission, and I’m so proud we got to publish it.

What are some other works, influential to you, that might serve as recommended reading?

Here are some books I’ve been thinking about lately: Trust by Hernan Diaz, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, Darkly: Blackness and America’s Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor, and ¡Hola Papi! by J.P. Brammer.

Describe the inspiration(s) for your book, Mad Prairie.

The stories fermented in my hometown in rural Kansas and took cues from my study of nineteenth century literature. I wanted to write a contemporary gothic work, full of smart, weird Midwesterners. The book is equally a new Winesburg, Ohio, and a reinvigoration of the gothic (Frankenstein, The Monk, Jane Eyre, The Turn of the Screw) for the twenty-first century.

Finally, tell us a bit about what you’re doing now!

I teach creative writing. I edit hex. I’m at work on a novel. I’ve also been writing flash. You can read my most recent flash at that other great Columbia, MO, magazine Wigleaf.

.